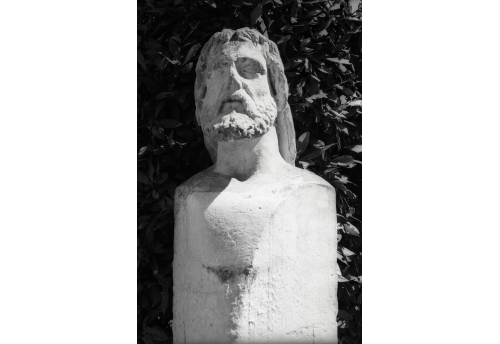

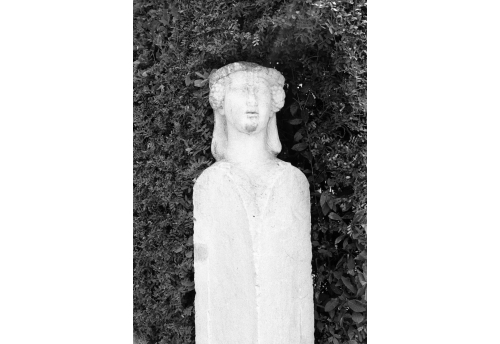

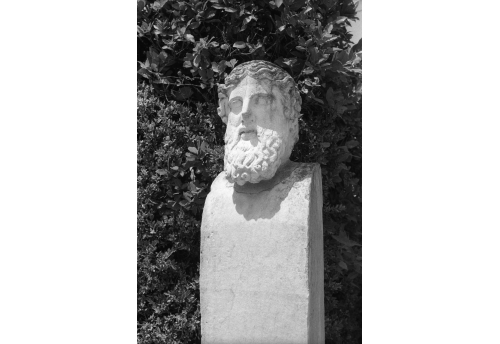

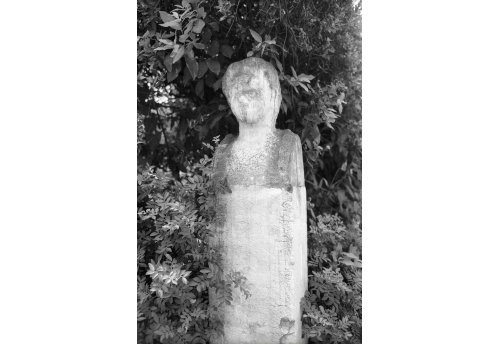

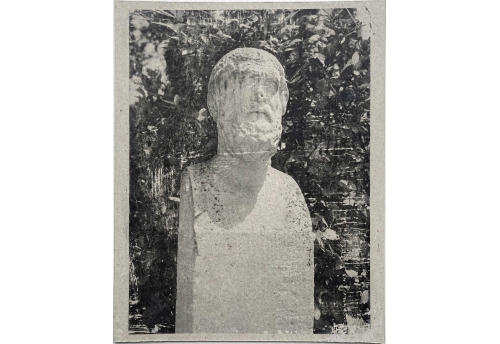

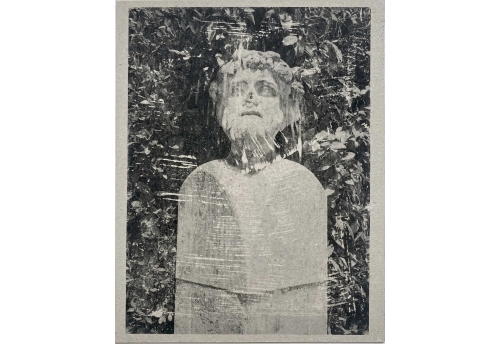

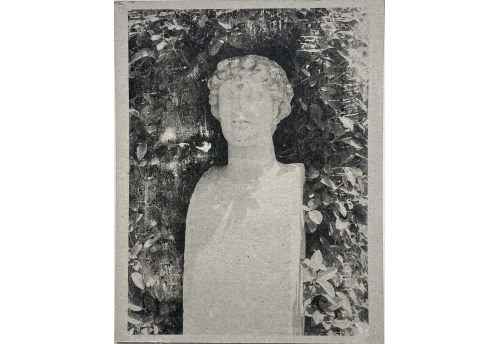

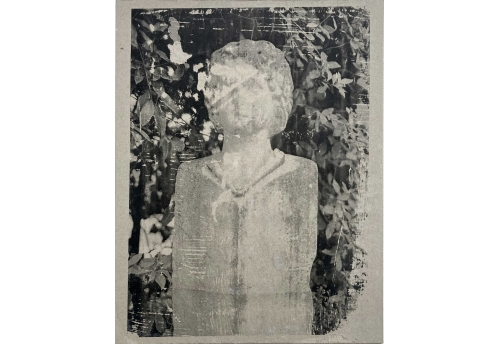

Born in Paris in 1984, Charlotte Bovy lives and works in Paris. After studying theater, she turned to photography. Her first images immediately reveal a sensitivity for black and white and question our relationship to time and especially to memory.

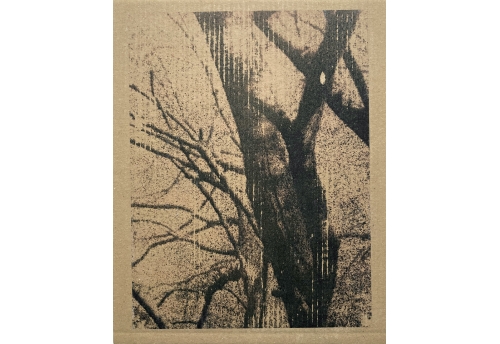

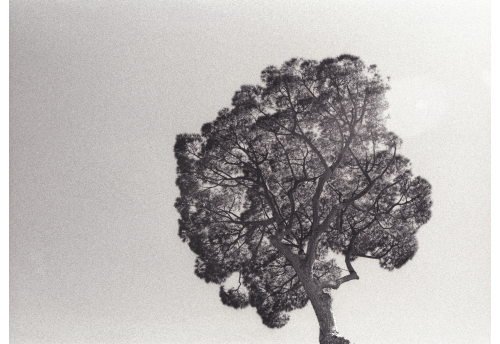

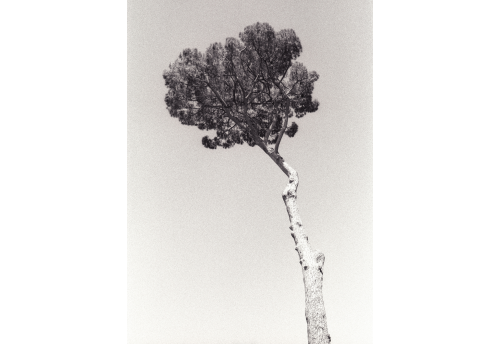

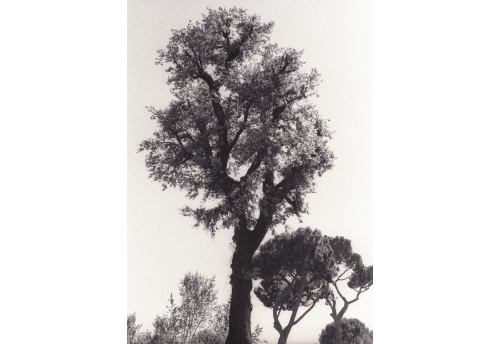

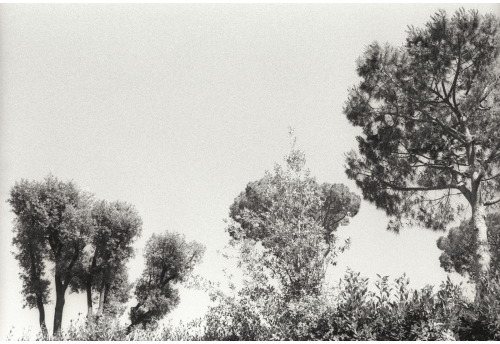

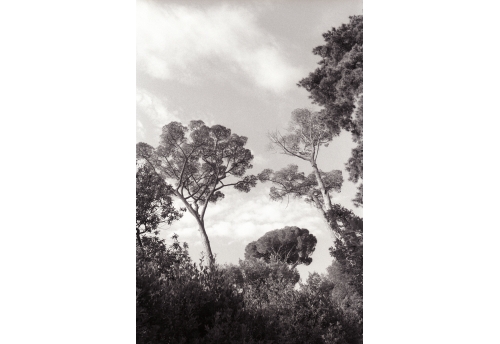

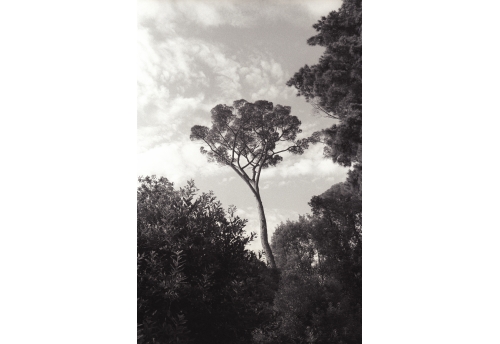

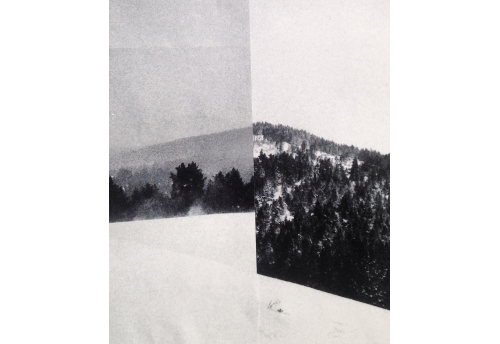

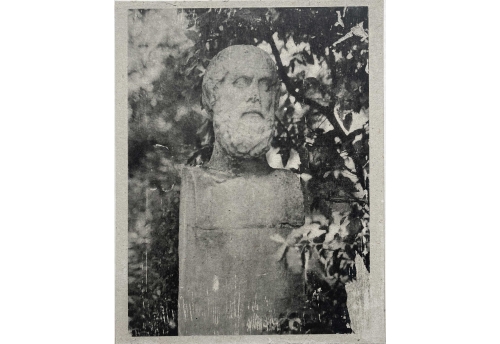

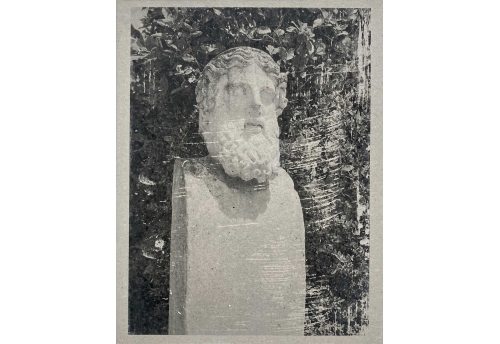

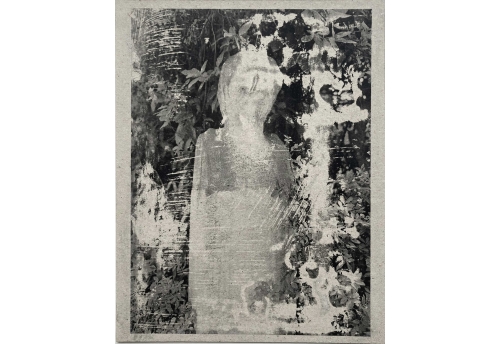

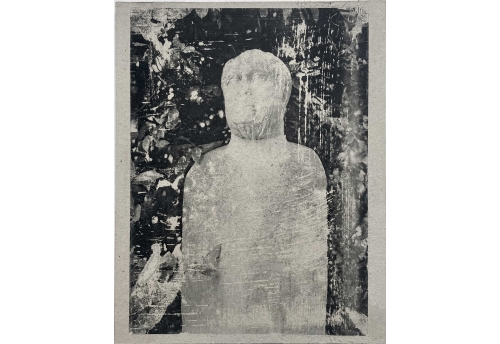

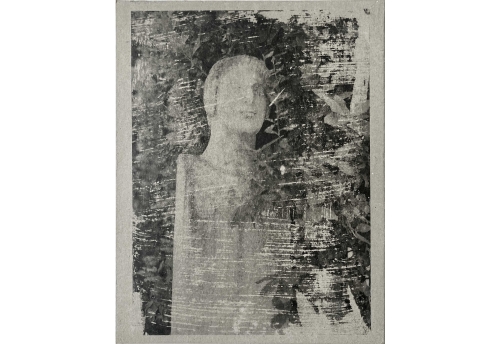

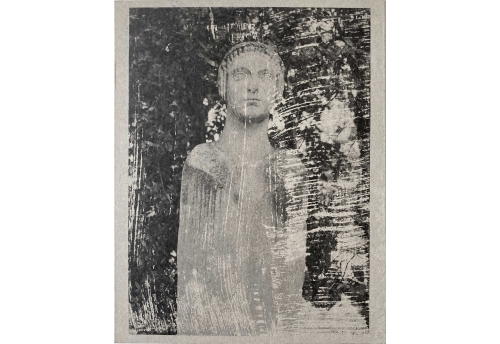

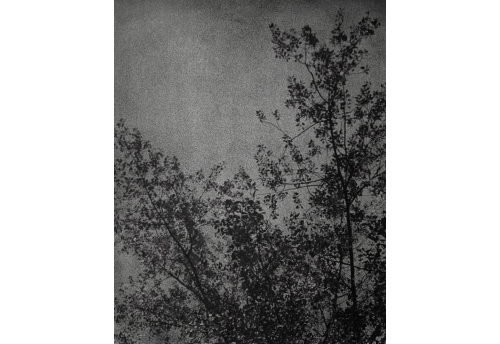

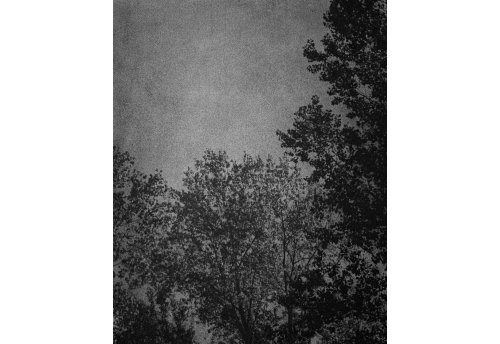

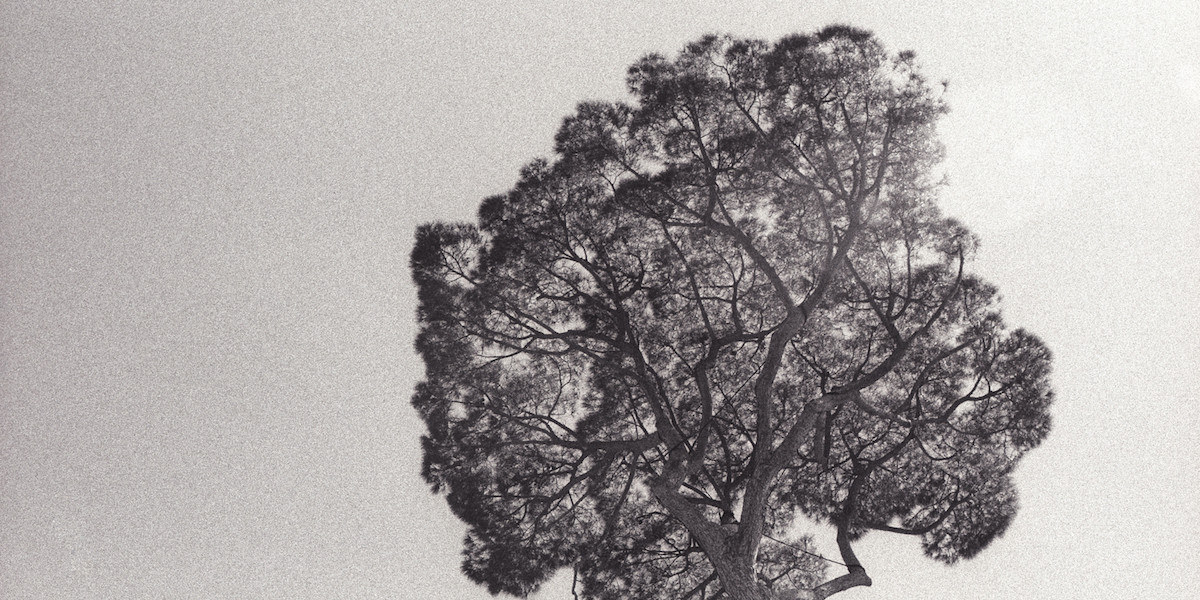

It is through the umbrella pines of the Villa Medici that Charlotte Bovy, a figure of the emerging photography, initiates her work around trees. On learning that some of them, so old that they knew the painter Ingres at the head of the institution, are going to be cut down, she decides to make portraits of these witnesses of the past, as one would of "old gentlemen". Her bias? To photograph them at the most overexposed hours in order to give their slender profiles the air of an apparition. With this series called "Solastagie", she experiments with a new transfer technique on a thick cardboard scraped and torn off in places. "Solastagie" is a concept invented in 2020 by an Australian philosopher, defining the distress felt in the face of environmental change. With this work, I cultivate an ambiguity: are we facing an image of the past or of a coming collapse?"

"Photography has something to do with resurrection" said Roland Barthes.

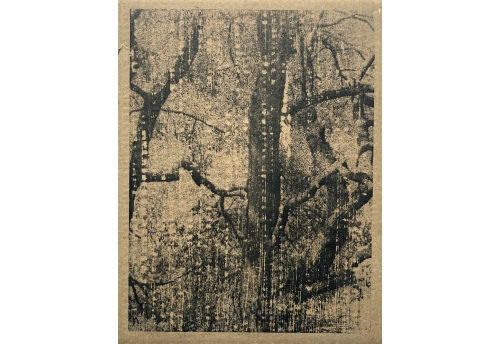

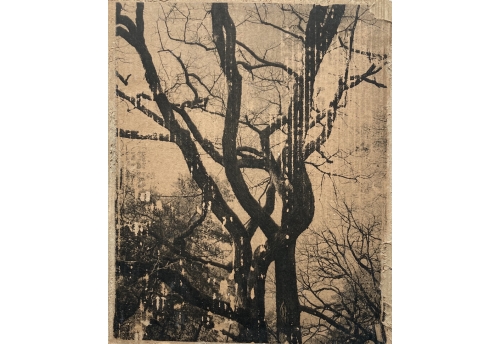

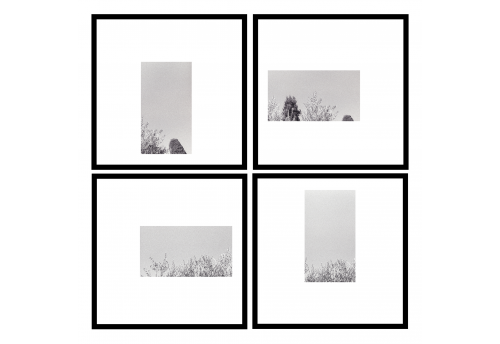

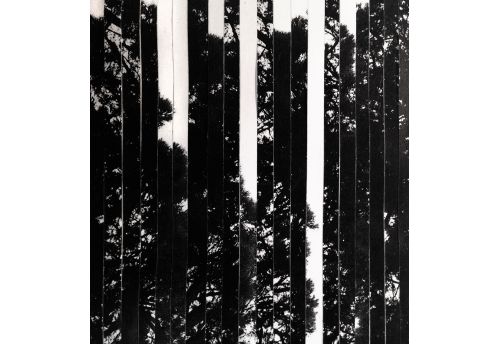

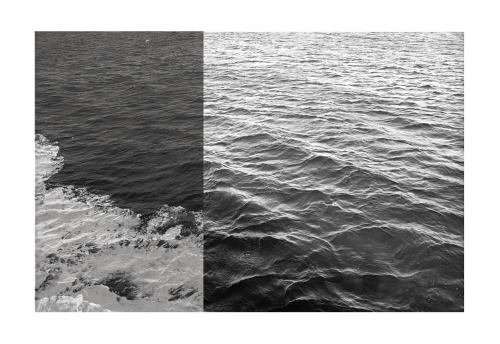

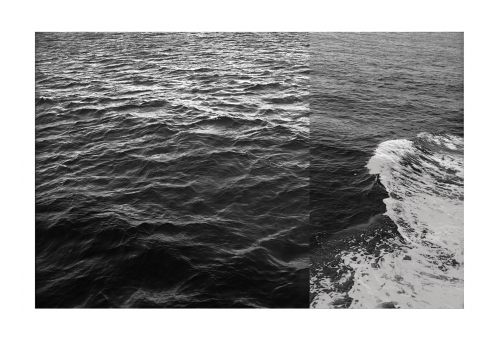

This series also revolves around an aesthetic research: re-framing the image, re-interpreting, re-seeing differently, re-composing. Here the photograph is a material to be reworked, unceasingly. From there any new construction is possible: a new look, a new image, a new story.

Each photograph is printed on watercolor paper with a (very) fine grain and makes the image tend towards the drawing.

"Charlotte Bovy was deeply touched by the planned felling of magnificent umbrella pines in Rome’s Medici gardens. She had a “sylvestrian revelation” as Ruskin would say, of the beauty and necessity of these exceptional living things. How could it be possible to cut down these monuments, great botanical clocks representing time towering over man? These edifices, the tired and tangled shapes as beautiful as temple ruins, should be preserved for the eyes of posterity. For several years now, she has been strolling in a wonderland of great trees and dreams, eyes wide open contemplating their leaves. Perhaps they might speak, like the oak oracles of the Dodona forest? Before her current Solastalgie series, one of her first series of images portrayed the trees of Normandy, where the oldest trees were to be found, such as the Allouville-Bellefosse pedonculate oak said to date back a thousand years. She went out to meet the great ancient forests of Normandy in the same way she would make the acquaintance of a living person, and took portraits of the “Old Normans” as the naturalist Henri Gadeau de Kervill did well before her in 1890s.

For this new series Solastalgie, the artist left Normandy and headed towards the Fontainebleau forest. This voyage isn’t without underlying meaning, as the young woman chose the forest of artists. As Théodore Rousseau wrote in 1852 in his letter to the Duke of Morny, asking him to intervene to prevent regulatory forest clearing, the Fontainebleau forest is “for artists that study nature the equivalent of models left by Michelangelo, Raphael, Correggio, Rembrandt, and all the other great masters.” Along with the painters came the “primitive” photographers – among others Gustave le Gray and Eugène Cuvelier.

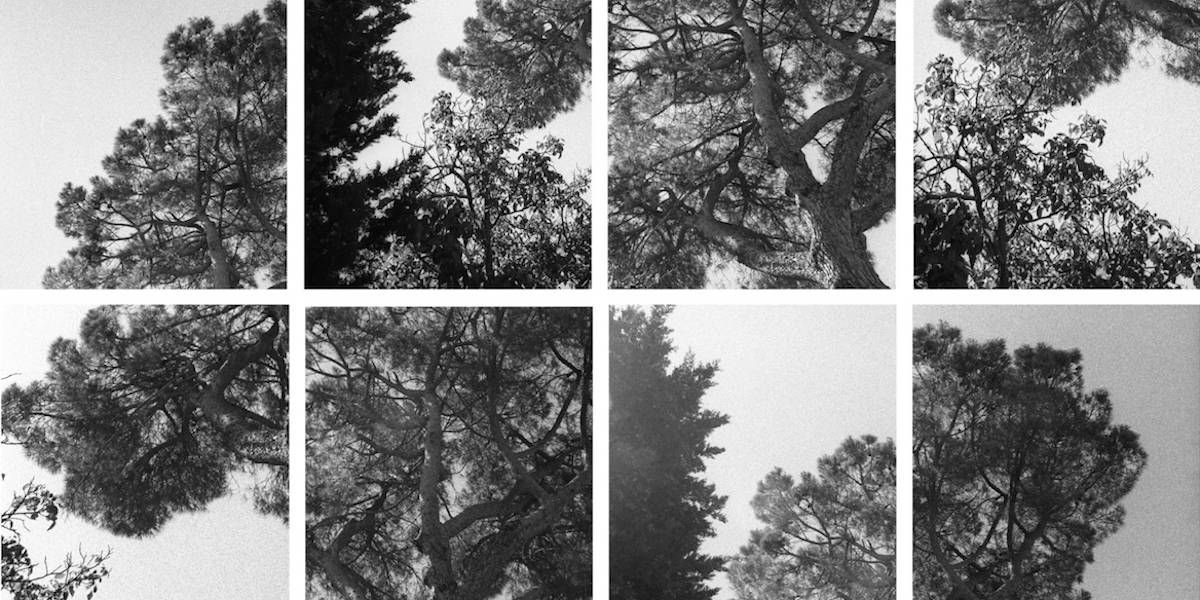

This forest, a matrix of the arts, is a challenge of scale for the young artist and contemporary photographer. How to enter into this life sized museum and measure up to the standards of those famous personalities who changed the way we see and perceive the tree? By using an orthogonal filter that seemingly multiplies viewpoints, Charlotte Bovey seeks to redefine the subject, to begin afresh, and in a certain fashion to take the measure of these great Fontainebleau monsters: overbearing, massive giants, and superbly clad. They are beautiful and enigmatic like a black and white full scale sketch “cartoon” used for creating a wonderful stained glass window that will one day adorn a cathedral. They shine with their own light, brought out by the overlaying grid, and which is reminiscent of the Renaissance technique used for scaling up images. Could this be a way of highlighting the grandeur of these tees, suggesting a promise of perpetual enlargement? Perhaps this geometric filter is a way to circumvent their wildness of form? Could there also be interplay between photography and drawing in this plastic interface? Black and white, a mix of contours and surfaces, Charlotte Bovy’s trees indeed represent an indefinite zone between drawing and photography. This might also be reminiscent of 19th century rivalries between these two artistic practices portraying this forest. "

Thierry Grillet