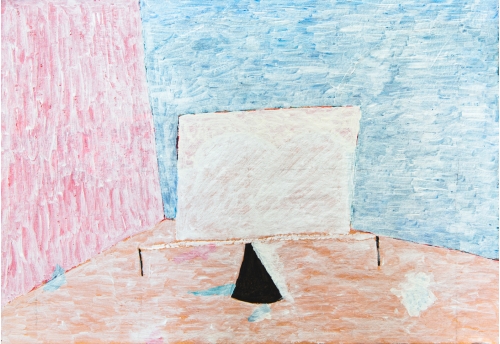

Pierre-Yves Canard is a collector, partly of the paintings he likes in the homes of other people (quotations and winks abound), partly of paintings which he would like to look in the home of other people, but which he does not find there. Therefore, he paints them.

Collector, he is also of the subjects which he inserts into his canvases, many subjects, titles and legends which evoke a world like the one of Raymond Roussel. Such as: Armchair, The Entomologist, Tintin, The Captive Crocodile, The Egyptian without pain, How to multiply your interior Plants, Orlando, Cat in Boots, Deer! Open to me! Naturalness is only a Pause among so many others, St Sebastien with Lemon, a place for each thing, Mythology for all,. ..

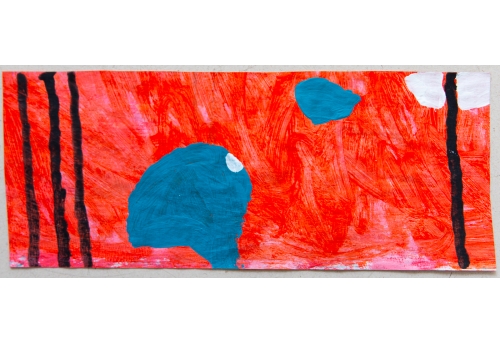

In "The Order of Things," Michel Foucault reports the existence of a "certain Chinese encyclopaedia", conceived by Borges, which has "the exotic charm of another thought, (...) shaking and worrying, for long, our thousand-year-old use of the Same and the Other". The taxonomy suggested in the text divides the animal world in: "a-belonging to the Emperor, b- embalmed, (...) d- piglets, (...) i- upset like an insane and (...) k- drawn with a very fine brush made out hair of camel." The headings denote conceivable categories in their singularities, but the inventory as a whole defies thought and makes it practically impossible. Not, by the way, because of the proximity of strange contrasts which it causes, and of the "proximity of the extremes or the things without relations"... No, what is impossible, is the site itself where they could exist. Precisely...

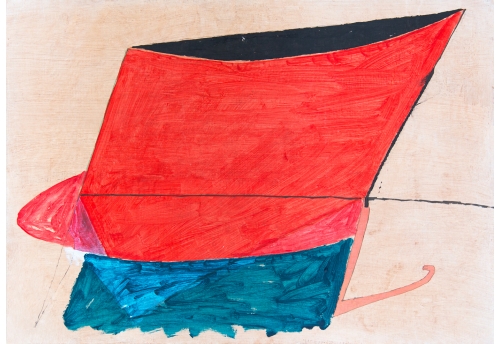

A painting is, for the collector, the privileged place for the cohabitation of these paradoxical singularities and an attempt of their classification: each canvas or drawing enters systematically into a topic, sometimes it crosses it or overlaps with another subject. These topics are not worked out according to the linear order of a series, as variations, and the various elements are not either fragments, or parts of a whole. They are meant to be what they are, and derive from different times and styles. No will to deepen, in the collector attitude, to work from underneath or to exploit a visual or a literary idea.

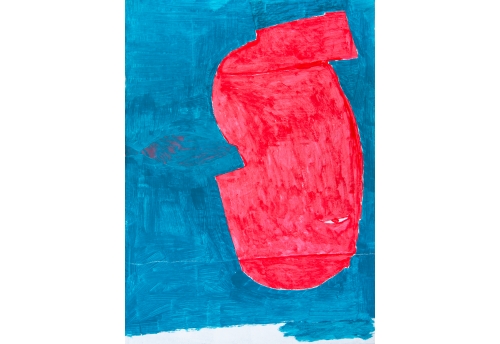

Tortoise and Armadillo , and other Chameleons , as they enter the canvas, seem ready to leap outside, actually they are already half-way out. It is also in this jumping quality, between these two moments, not clear which is one or the other, entry or exit, that the temptation of a fable emerges, just appearing, already disappearing. The refusal of a narrative is categorical!

The subject is firmly anchored in the space of the canvas, but it floats, it remains in suspension. The will of the collector is obvious in what he presents: a wavering, partly created by a certain ambiguity.

"The ambiguity, says the collector, is the only way of breaking the conventional relation of recognition and habits which one upholds with things, phenomena and people. This is also the only way to suggest the interior, offering a show between two elements, two possibles."

And also:

"I hardly believe in experience, the little we know is printed into us like by a plug stamp."

That is, there is little desire to seek information, knowledge, little desire to create , but rather to reconstitute a puzzle.

One might relate this desire to that of the son of Marguerite Duras: "I do not want to go to school any more because I learn things that I do not know."

Christiane Cavallin Carlut, October 2005