After a weekend punctuated by the alerts of Le Monde and the tired faces of the presenters of BFMTV, it seemed obsolete and inappropriate to talk about anything other than the bloody offensive of Russia in Ukraine. The heart is not in the matter. It remains blocked at the other end of Europe in this country which surprises and impresses us by its courage and its determination to preserve its freedom. If these few days of endless scrolling on social networks have taught us anything, it is the strength of the Ukrainian people, its History so special and its culture so singular.

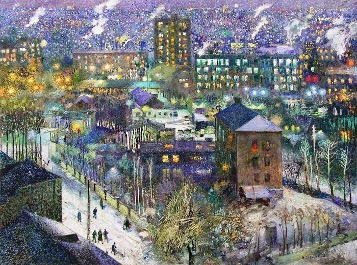

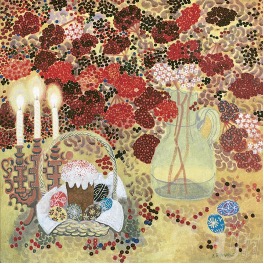

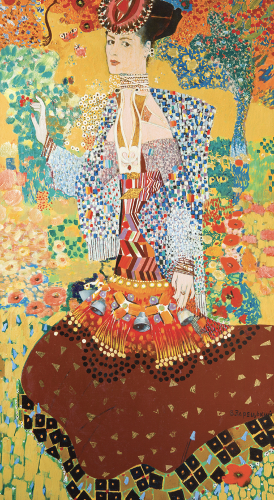

At the bend of an Instagram post appears a painting that we do not recognize. The caption presents Viktor Zaretsky, considered one of the greatest Ukrainian painters of the twentieth century. If this name does not tell us anything, the pictorial work, the colors, the silhouettes, evoke us the characteristics so distinctive of the father of Viennese symbolism, Gustav Klimt. Indeed, we find this fantastic, lively, luminous world, close to that of Klimt. However, Zaretsky adds much of his own creativity. In particular, elements of Ukrainian folklore, backgrounds composed of mosaics of precious stones or fanciful floral patterns, as well as female figures of breathtaking beauty. Princesses of children's dreams or Egyptian queens, Zaretsky mixes in his models the features of the women of Diego Velazquez, the mystical paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites or the paintings of Gustav Klimt. But far from being pale copies, Zaretsky's paintings are symbols of a unique and independent Ukrainian style, freed from the shackles of Socialist Realism, a doctrine in which the work must reflects and promotes the principles of Soviet-style communism.

Viktor Zaretsky and his wife Alla Horska, also a painter, were early members of the Ukrainian dissident movement The Sixtiers. Alongside writers, poets, intellectuals and artists, they advocated the development of the Ukrainian language and culture and refused to let their works serve the interests of the Soviet authorities. Over the years, the fight of the "Sixtiers" became more and more violent. Some artists are deported or locked up, others are physically attacked. Zaretsky himself paid for his commitments and convictions when, in 1970, he lost his father and his wife on the same day. Zaretsky's father allegedly killed his stepdaughter and then committed suicide by throwing himself under a train. However, many inconsistencies in the case indicate that it was all fake. Alla Horska's family and entourage were convinced that her murder was carried out by the KGB, as was Zaretsky's father one.

As despair and depression gripped the artist, he decided to turn to the light. His painting then takes a new turn. He puts all his hopes, all his dreams, all his desires on canvas. The colors become richer and richer, brighter and more alive. He paints all this life that he couldn’t live with those he loves and loved. And step by step, his paintings are approaching the work of Gustav Klimt.

The Ukrainian art historian Olesya Avramenko, explains that Zaretsky did not see Klimt as a "guru" or as a spiritual and artistic master to be followed and copied, but rather as a companion in the struggle and an ideological colleague who came to similar artistic conclusions and achievements in his work. Zaretsky saw in Klimt his own alter ego, he found in his work the full experimentation of something he had looking for all his life : creative freedom without ideological limitations.